California Told Companies to Label Toxic Chemicals. Instead They’re Quietly Dropping Them

Businesses are making moves to avoid consumer warning labels, and the effects reach far beyond California

Requiring warning labels on products with potentially toxic ingredients can obviously help keep them out of a careful consumer’s shopping cart. But a recent study shows that these “right-to-know” laws may also halt such formulations long before they hit the shelves or are released into the air—and can even protect people outside a law’s geographic range.

One of the most significant such laws ever passed in the U.S., California’s Proposition 65, requires businesses to post a warning when chemical exposures, whether through product ingredients or air emissions, exceed a safe standard. For the recent study, published in Environmental Science & Technology, researchers interviewed business leaders and found that California’s rule has caused many companies to reformulate their products by reducing amounts of flagged ingredients to safer levels—or by dropping them entirely.

The interviews covered dozens of industries such as cleaning products, electronics and home improvement. They included top-earning brands across all sectors as well as leading green cleaning brands—although the companies remain anonymous in the study, says lead author Jennifer Ohayon, a scientist at the nonprofit research organization Silent Spring Institute.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Ohayon and her colleagues found that companies commonly replaced the warning-requiring ingredients altogether, in part to avoid possible litigation. Michael Freund is a lawyer who spent decades representing groups aiming to stop toxic chemical emissions; he says the California proposition’s incentives can help fill a key gap. In the cases he worked on, “every one of those companies had permits that allowed them to do what they were doing,” he says. “And that’s where Prop 65 comes into play.”

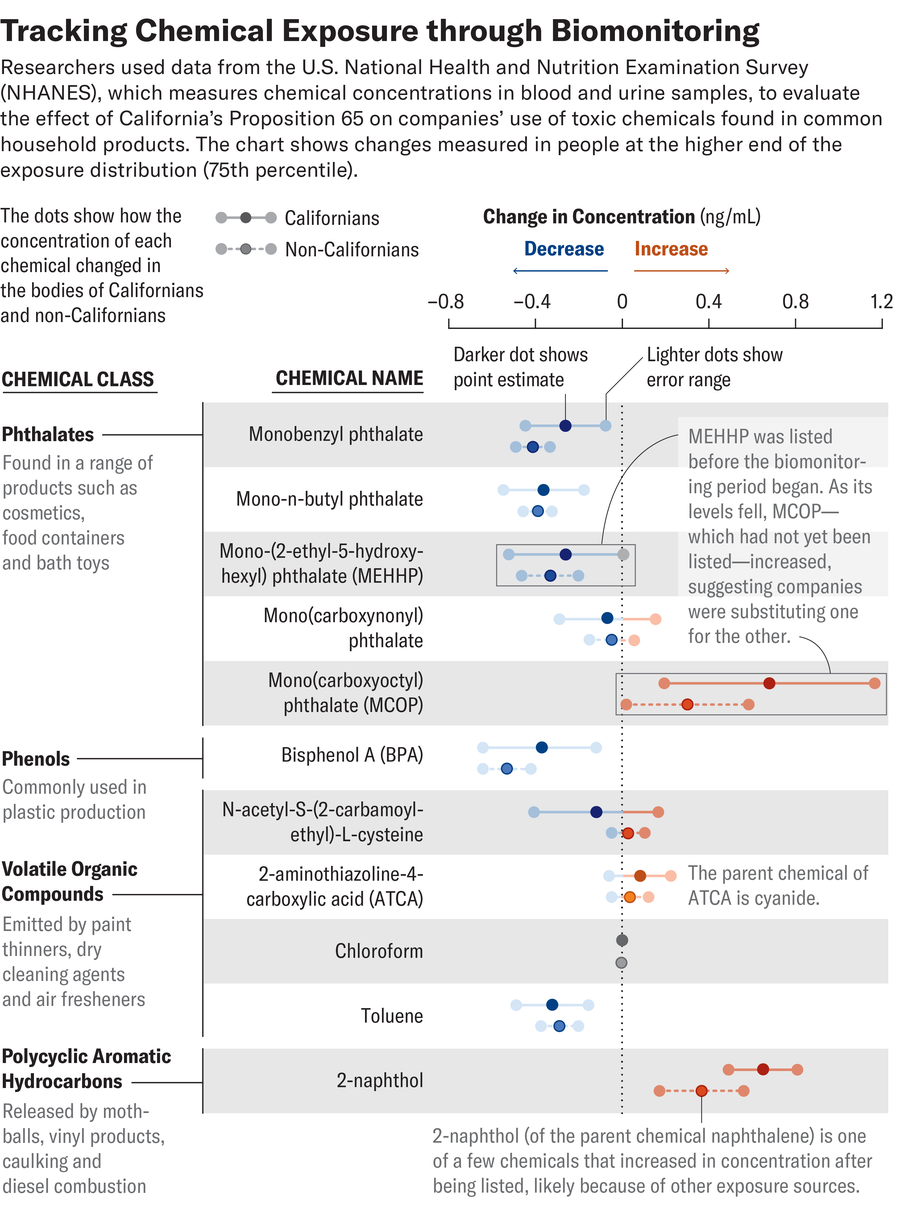

Ripley Cleghorn; Source: “Trends in NHANES Biomonitored Exposures in California and the United States following Enactment of California’s Proposition 65,” by Kristin E. Knox et al., in Environmental Health Perspectives, Vol. 132, No. 10; October 2024 (data)

Although the 1986 law is specific to California, the study results suggest its effects cross state borders as manufacturers reformulate their products nationally. A parallel study published last year by the Silent Spring Institute backs this idea up with data. That study looked at levels of 37 chemicals in blood and urine samples among both Californians and non-Californians. Of the chemicals, 26 were listed in Prop 65, and samples from before and after listing were available for 11 of those, which allowed for a comparison. For most of the chemicals, levels in people’s bodies decreased after listing—both in California residents and across the nation.

Megan Schwarzman, a researcher involved in both studies, says sample data exist for only a tiny fraction of the 900 Prop 65 chemicals. In a metaphorical game of Twister, the researchers had to figure out what publicly available data could be matched to Prop 65 chemicals because “the data weren’t collected for that purpose,” Schwarzman says. Monitoring all listed chemicals over time in future work would show any patterns much more clearly.

The new study notes that Prop 65 is sometimes criticized for leaving Californians “over-warned” and “under-informed.” But the research so far suggests that regardless of consumer effects, the policy has guided at least some businesses’ choices—raising the bar for everyone.