New Plan for Particle Physics Megaproject Leaves out Funding Details

A long-awaiting report from CERN explores the feasibility of building a supersized successor to the Large Hadron Collider

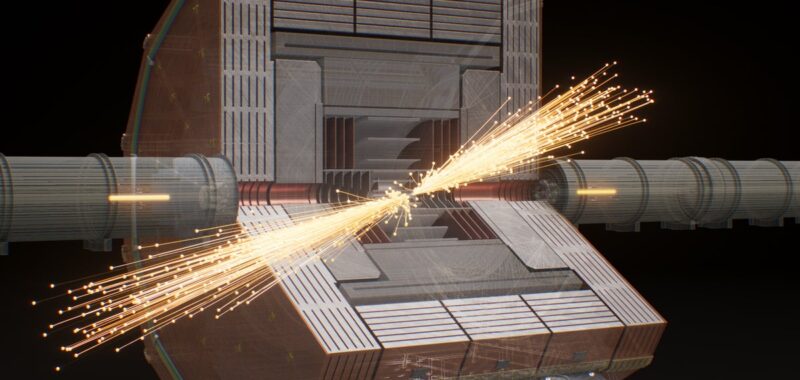

The Future Circular Collider (artist’s impression) would initially smash together electrons and their antiparticles, positrons.

CERN’s ambition to build an accelerator three times as large as the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) took a significant step forward on 31 March with the release of a massive feasibility study for the project. But possible scenarios for how to fund the new machine will be presented at a later date.

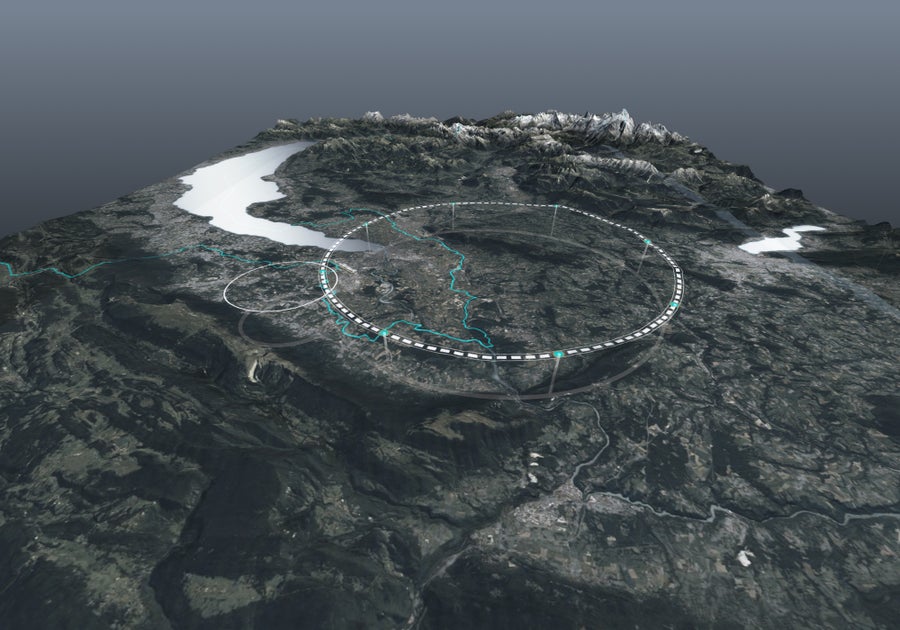

The European particle physics laboratory near Geneva, Switzerland, has not yet officially decided whether to endorse the 91-kilometre Future Circular Collider (FCC) project or other options for new colliders, but the study will feed into a review of CERN’s long-term strategy that is due to conclude next year.

“This study is the result of an immense amount of work carried out by the international FCC collaboration,” said Fabiola Gianotti, CERN’s director general, in a presentation to reporters. “If approved and implemented, the FCC could become the most extraordinary instrument ever built by humanity to study the laws of nature at the most fundamental level.”

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Grand designs

The three-volume feasibility study, to which around 1,500 physicists and engineers have contributed, estimates that it would cost 15.32 billion Swiss francs (US$17.4 billion) to dig a 91-kilometre-long circular tunnel and build a machine to smash together electrons and their antiparticles, positrons, by the mid-2040s. This would enable high-precision studies of the Higgs boson and other known particles.

A second stage for the project—which would reuse the tunnel and collide two beams of protons, like the LHC—would would not come online until 2072 at the earliest, and would cost 18.8 billion Swiss francs to build. That estimate is based on the assumption that the proton collider will operate at 85 Tera-electronvolts (TeV)—an energy six times higher than the LHC, but lower than the 100 TeV that was proposed initially. Gianotti told reporters that this was a conservative assumption based on using the high-field superconducting magnets—needed to steer protons around the ring—that are available today. Ongoing research on advanced superconducting materials could put higher energies within reach for the 91 km tunnel, perhaps even 120 TeV.

CERN Council president Konstantinos Fountas told reporters that the study will provide “very solid ground” to enable the Council to come to a well-informed decision on whether to go ahead with the project. Antonio Zoccoli, president of Italy’s National Institute of Nuclear Physics and one of country’s delegates to the CERN Council, agrees, saying that the group has done “very solid work” on the technical design and cost estimates.

Vladimir Shiltsev, an accelerator physicist at Northern Illinois University in DeKalb, says the cost estimates are broadly in line with those he and his collaborators made in a 2023 study that compared various collider proposals. He says the authors of the feasibility study wrote a “very nice, solid, comprehensive document,” although a few technical questions remain unanswered.

A CERN map shows where a 91-km circular tunnel might be dug; the smaller LHC is to its left.

Gianotti said that CERN could cover 65% of the construction cost for the first stage of the project from its existing budget. That would still leave a shortfall of more than 5 billion Swiss francs, which would need to be covered with additional contributions. The feasibility study had been asked to provide funding scenarios for the project, but this information will now be provided at a later date, she said.

CERN initially budgeted CHF100 million for the feasibility study itself, and a CERN spokesperson told Nature that the final cost was CHF113 million (US$128 million).

The FCC plan has its critics. Some physicists believe that the scientific goals of the first stage could be achieved with a smaller, cheaper linear collider, and many are put off by the timeline for the second-stage proton collider. “Both the member states and the science community will feel that they are being locked into something like a 70-year mortgage, if they agree to go ahead,” says John Womersley, a special advisor to the University of Edinburgh, UK, who is a former UK delegate to the CERN Council. “Almost no one that I have spoken to thinks this is a good idea.”

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on April 1, 2025.