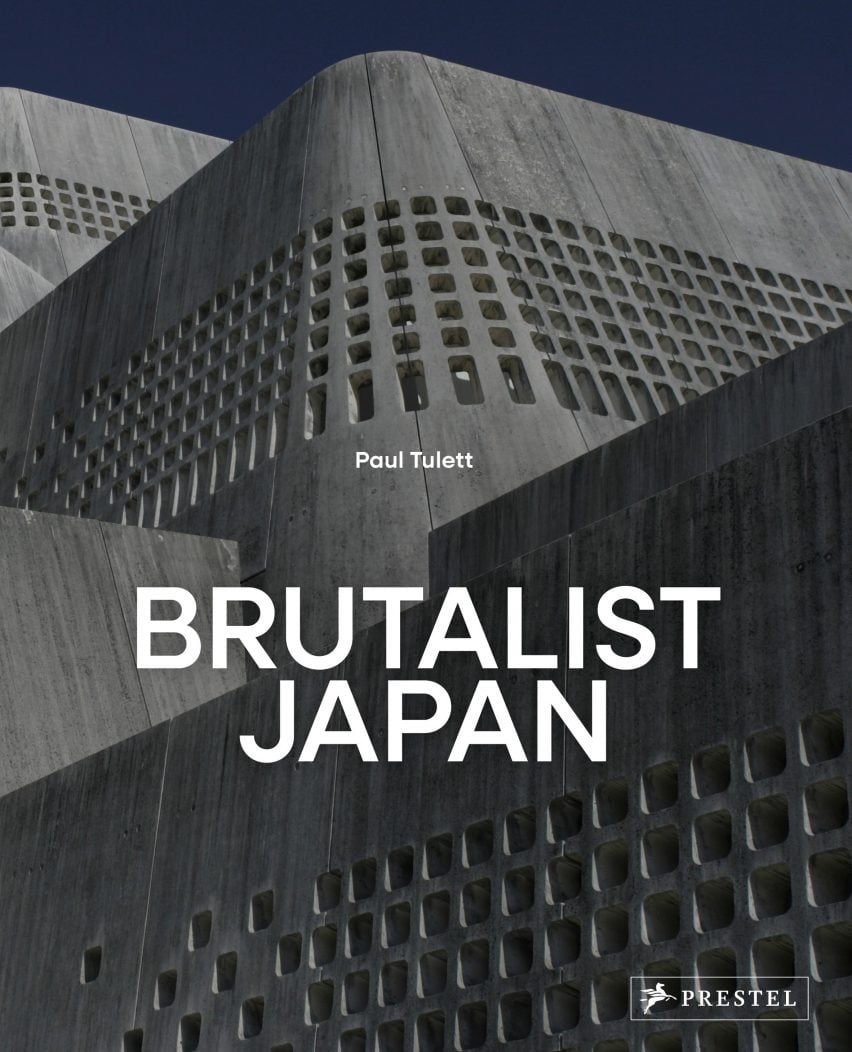

Photographer Paul Tulett has toured Japan to publish a book documenting the country’s vast collection of concrete edifices. Here, he spotlights nine unusual examples featured in it.

The book, fully titled Brutalist Japan: A Photographic Tour of Post-War Japanese Architecture, has been published with Prestel to showcase the diversity of the country’s brutalist buildings.

It was the result of Tulett’s growing interest in the style of architecture, which he said has a “unique tactility” in Japan thanks to its links to the country’s traditional carpentry and craftsmanship.

“Upon arriving in Japan, I was struck by the abundance of brutalist buildings, their refinement and the fact that no one was really covering the style here,” he told Dezeen.

“I quickly became interested in brutalism’s links to traditional Japanese architecture,” Tulett continued. “The refinement in Japanese brutalist construction is due to the amazing timber formwork seen here. It results from incredible expertise in carpentry within the nation.”

All the buildings featured in the book were photographed by Tulett over the last five years and selected to showcase the range of styles that fall within Japanese brutalism.

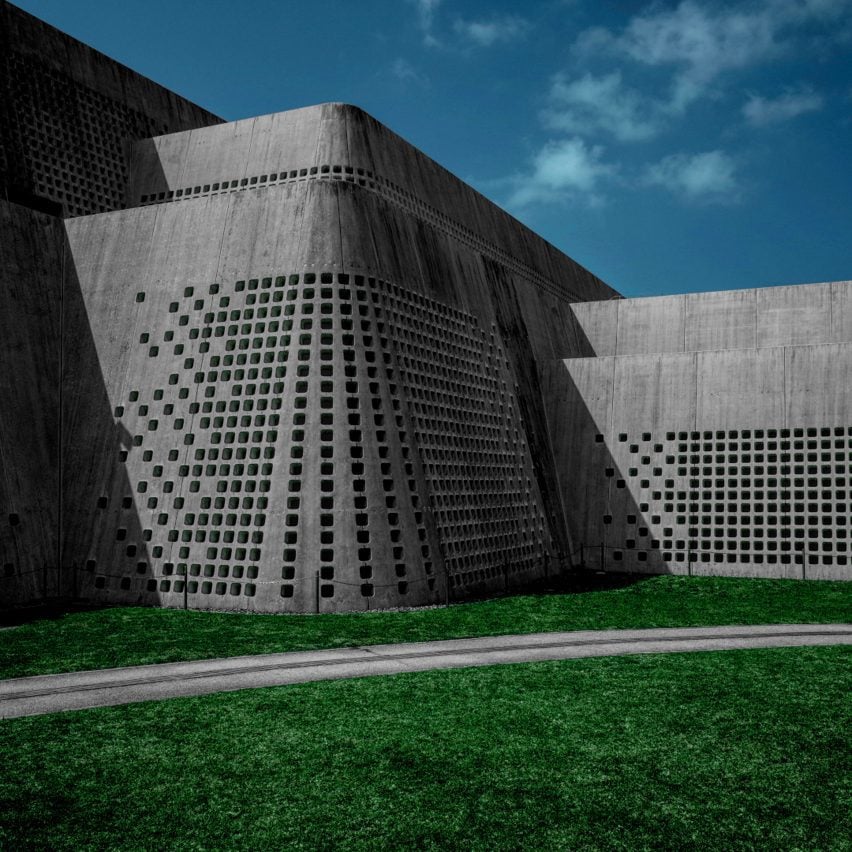

One of Tulett’s favourite examples is the brutalism in Okinawa, where he is based, which he said incorporates traditional breezeblocks to mimic chinibu – a traditional perforated wall used to provide both ventilation and protection from harsh sunlight.

“I wanted to present the diversity of Japanese brutalism in terms of function, size, style, design and age,” Tulett explained. “From large civic and governmental buildings to small barber shops and public toilets, the diversity of function is not seen elsewhere.”

Tulett’s aim was for the book is to spark interest in the style of architecture, which he said is “too often demolished based on the subjective opinion of a few individuals”.

“Many brutalist buildings across the world are slated for demolition at a time when there is increasing fascination with the style – particularly amongst younger generations,” said Tulett.

“Brutalist buildings in Japan, even the grandest, are not immune to talk of demolition. These include Hiroyuki Iwamoto’s sublime National Theatre in Tokyo, Kenzo Tange’s incredible Kagawa Prefectural Gymnasium and the fantastic Nago City Hall in Okinawa.”

I aim to inspire an appreciation for the aesthetic beauty of these structures while fostering discussions around their preservation. Ultimately, I advocate for the continued recognition and preservation of this often misunderstood architecture.”

Read on for Tulett’s picks of nine unusual buildings featured in Brutalist Japan:

Kagawa Prefectural Gymnasium, 1964, by Kenzo Tange

“Concurrent with Kenzo Tange’s creation of Tokyo’s mammoth Olympic structure for the 1964 Summer Games, a humbler athletic vessel was birthed further west.

“Between 1962 and 1964, the Kagawa Prefectural Gymnasium arose in Takamatsu, with a brutalist silhouette strong enough to renounce any kinship with its neighbours.

“An oval hull is hoisted by four titanic columns, extending its form in a defiant cantilever that bestows upon it the visage of a seafaring leviathan, mirroring both the formidable might and grace of an Olympian.”

Kyoto International Conference Center, 1966, by Otani Sachio

“Enshrined amidst Kyoto’s venerable aura, the Kyoto International Conference Center straddles the architectural zeitgeist of its time.

“This edifice stirs a lively discourse: does it belong to the brutalist canon, or does it bear the hallmark of metabolist architecture? The centre’s silhouette, a composition of bold geometric lines and the stark honesty of exposed concrete, channels the brutalist ethos.

“Its colossal, forthright forms stand in sharp relief to Kyoto’s delicate tapestry, an assertion of brutalism’s unapologetic gravitas. Yet, within its robust frame, the structure nurtures the flexible, organic essence of metabolism.”

Nago City Hall, 1981, by Team Zo (Elephant Design Group)

“This tumbling agglomeration of colonnades, pergolas and terraces set upon a floor plan resembles the outline of a B-2 stealth bomber.

“The colonnades are formed of porous vermillion and grey concrete blocks. Tilted concrete screening slats set within the pergola roofs absorb ambient moisture and provide a breeding ground for moss.

“The whole structure exudes an earthy pungency that is tempered by the fragrance of weaving bougainvillaea. Drinks vending machines aside, the place smacks of an undiscovered jungle ruin.”

Nago Civic Hall And Center, 1985, by Shiro Ochi

“This is a U-shaped complex of civic centre, public halls and general welfare centre. Recognisable modernist features contrast with its mad tree-hugging neighbour – the City Hall above – and evoke a Corbusian rationality triumphing over nature.

“Reminiscent of Mayan architecture, a sharply terraced escarpment is carved down to the northern and western flanks of what would otherwise be a trapezoidal behemoth.

“The exterior austerity is juxtaposed by intricate interior precast trusses and sublime modulated concrete slabs on either side of the stage. These emanate a peachy hue that compliments the velvety seating.”

Mixed-use complex, 1994, by Kuniyoshi Design

Darth Vader’s holiday home? Nah. This striking complex features affordable housing stacked above a ground-floor elderly daycare centre.

“It models Okinawa’s social aspect of planning, more characterised elsewhere by the interests of private developers. This planning philosophy seeks to create urban spaces that nurture community bonds and ensure equitable access to resources.

“That said, a friend of mine had the opportunity to move into one of the apartments but his wife declined, arguing it wasn’t close enough to a convenience store. Definitely grounds for divorce.”

Keihan Uji Station, 1995, by Hiroyuki Wakabayashi

“In the shadow of tradition, where the air hums with tales of ancient temples and the crackle of fireworks over the Uji River, Keihan Uji Station emerges like a scene from a sci-fi odyssey.

“This architectural spaceship, helmed by visionary captain Hiroyuki Wakabayashi and launched in 1995, defies its historic backdrop with a daring leap into futurism.

“The design is audacious, a semicircular cocoon that dares to embrace both the circle’s zen-like simplicity and the boundless possibilities of the cosmos. It is quite possibly my favourite building.

Kihoku Astronomical Museum, 1995, by Takasaki Masaharu

“Clearly in the throes of his Smack My Bitch Up phase, architect Masaharu took inspiration from the moon crab on The Prodigy’s The Fat of the Land album cover.

“From certain angles, this Cancerian creature seems to be embracing the stars in rave-like rapture or wondering where it left its whistle and helium balloon.

“Actually, the design slightly predates The Prodigy’s third album. More cerebral appraisals cover Masaharu attempting a cosmic connection between Earth and the universe. A participatory approach allowed for the local community to showcase the potency of the region’s mushrooms.”

Okinawa Prefectural And Art Museum, 2007, by Ishimoto and Niki Associates

“The Naha Prefectural Museum appears as both a cascading, multi-tiered limestone waterfall and immovable monolith – the result of a geological phenomenon aeons ago.

“Its appearance borrows from ancient Okinawan fortresses, or gusuku, yet is simultaneously futuristic with gentle curves, rectilinear geometry and stacked forms.

“A look of natural stone is achieved through the use of white cement – local limestone as the coarse aggregate and coral sand as the fine aggregate. Doctor Who fans might see a Dalek and the more domesticated an upturned laundry basket. I see it as my muse.”

Matsubara Civic Library, 2019, by Maru

“Beside a tranquil pond, the Matsubara Civic Library rises like a tome from the annals of time, its spine crafted from 600-millimetre-thick concrete.

“The architects, in a stroke of narrative genius, penned a story of integration rather than erasure, allowing the library to float out into the water like a literary ark.

“Inside, the seismic-resilient walls have inscribed freedom into the library’s chapters, with split levels that unfold storeys upon storeys, where readers perch like characters in a plot, poised between lines of text and water.”