The Cardboard Cathedral in New Zealand by Japanese architect Shigeru Ban is the next building to secure its place in our list of the 25 most significant buildings of the 21st century.

Cardboard is unlikely to spring to mind for most when considering materials suited to building a cathedral, yet it is exactly what Shigeru Ban opted for when creating one in Christchurch in 2013.

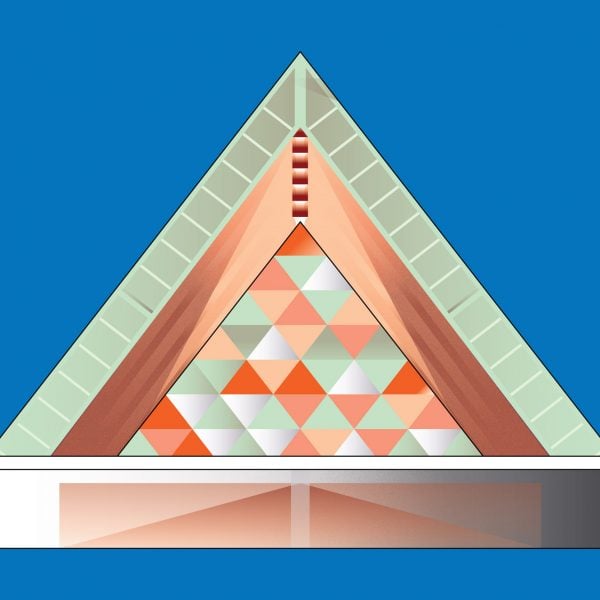

Defined by its steep A-frame, the Cardboard Cathedral, known officially as the Transitional Cathedral, is formed of 98 cardboard tubes combined with wood and polycarbonate.

It was designed by Ban as a pro-bono project following the deadly magnitude 6.3 earthquake on New Zealand’s South Island in 2011.

Remarkably, it was only ever intended to be temporary, but it quickly became one of New Zealand’s most iconic buildings, offering citizens a symbol of resilience and hope.

The 2011 Christchurch earthquake and its aftershocks tore through the city, claiming the lives of 185 people and destroying numerous buildings, most notably its landmark Anglican cathedral.

Ban’s replacement for the cathedral, realised with local studio Warren and Mahoney, was the first non-commercial structure to be built in the city centre after the disaster. It was only intended to remain in place until a more permanent cathedral was constructed – a controversial subject that divided critics and saw many people call for the original building to be restored.

The building’s innovative construction and its impact as a first major sign of new life seem to have captured the collective imaginationAndrew Barrie in the Architectural Review

However, despite these circumstances, the cardboard cathedral was soon identified as an icon that encapsulated the city’s revival, ultimately cementing its place there.

In his review of the building in 2014, architecture critic Andrew Barrie suggested that the impact of the structure on the earthquake-ravaged city was immediately visible.

“The building’s innovative construction and its impact as a first major sign of new life seem to have captured the collective imagination, and the now permanent structure seems set to become an enduring symbol of Christchurch’s revival,” Barrie wrote in a piece for the Architectural Review.

“Even before its completion, it had begun to replace the old neo-Gothic cathedral as a symbol of the city, appearing in national television advertisement among iconic city scenes from around the country,” Barrie added.

“Ban’s project serves as a reminder not only of the way that Japan and New Zealand were united in loss, but also of the potential that may yet be unlocked in the common task of rebuilding.”

Perhaps this outcome was expected by Ban, who previously stated that “if a building is loved, then it becomes permanent”.

“The lifespan of a building has nothing to do with the materials. It depends on what people do with it,” he once told the Guardian.

“If a building is loved, then it becomes permanent. When it is not loved, even a concrete building can be temporary.”

The Cardboard Cathedral’s A-frame is formed of 98 cardboard tubes filled with wooden structural beams and raised on walls formed from eight shipping containers. A polycarbonate roof crowns the structure.

Its structure is animated at one end by a large coloured-glass window, formed from a patchwork of triangles that illuminate the worship space for 700 people.

Though it occupies a different plot – one approximately a 10-minute walk away – Ban based the form and scale of the building on the original cathedral to offer visitors a sense of familiarity.

Inside, the worship hall is filled with matching cardboard furniture, designed by Ban, including a cardboard tube pulpit.

For some, the most striking factor about Ban’s choice of cardboard is that the cathedral replaces a Gothic revival-era structure, in a place nicknamed a garden city because of its traditional architecture that bears a resemblance to towns in England.

It is perhaps this very juxtaposition that makes the Cardboard Cathedral so impactful, illustrating the value of breaking convention and testing materials and proving that contemporary and traditional design can co-exist.

It also demonstrates that architecture does not have to be extravagant and resource-intensive to be valuable and long-lasting.

“The quality of the building doesn’t depend on the quality of the materials,” Ban once said when discussing the project. “It depends on the quality of the space that is created by volume, light and shadow.”

Financial Times critic Edwin Heathcote described the building as “remarkable”.

“It is one of the most remarkable, uplifting and joyful churches I have seen, one that takes an almost childlike pleasure in its chunky tubes, elemental building-blocks form and translucent surfaces,” wrote Heathcote.

For those familiar with Ban’s work, his choice of cardboard for the project will not have come as a surprise.

The cathedral is a large-scale evolution of the lightweight and low-cost shelters that he has created with cardboard tubes for disaster victims around the world – most recently in Europe to house Ukrainians fleeing the Russian invasion.

It also follows the architect’s cardboard-tube chapel in Japan, built after the Great Hanshin earthquake in Kobe in 1995 and later relocated to Taiwan.

As demonstrated by his work, cardboard is a material well-suited to these seismic zones, as it can withstand quakes that might destroy heavier structures built from concrete. Additionally, it lends itself easily to disassembly and reassembly.

“The strength of the materials is unrelated to the strength of the building,” Ban once told the Japan Times. “The first time I used paper was for an interior, but I realised it was strong enough to be used as a structural element – to actually hold up the building.”

Today, the cardboard cathedral is arguably one of Ban’s most lauded projects and just one year after it was completed, he was awarded the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize.

In his announcement, the former Pritzker Architecture Prize jury chairman and British property developer Peter Palumbo hailed Ban as “a force of nature.

“This is entirely appropriate in the light of his voluntary work for the homeless and dispossessed in areas that have been devastated by natural disasters,” Palumbo said.

But he also ticks the several boxes for qualification to the Architectural Pantheon – a profound knowledge of his subject with a particular emphasis on cutting-edge materials and technology; total curiosity and commitment; endless innovation; an infallible eye; an acute sensibility – to name but a few.

Did we get it right? Was the Cardboard Cathedral by Shigeru Ban the most significant building completed in 2013? Let us know in the comments. We will be running a poll once all 25 buildings are revealed to determine the most significant building of the 21st century so far.

This article is part of Dezeen’s 21st-Century Architecture: 25 Years 25 Buildings series, which looks at the most significant architecture of the 21st century so far. For the series, we have selected the most influential building from each of the first 25 years of the century.

The illustration is by Jack Bedford and the photography is by Stephen Goodenough.

21st-Century Architecture: 25 Years 25 Buildings

2000: Tate Modern by Herzog & de Meuron

2001: Gando Primary School by Diébédo Francis Kéré

2002: Bergisel Ski Jump by Zaha Hadid

2003: Walt Disney Concert Hall by Frank Gehry

2004: Quinta Monroy by Elemental

2005: Moriyama House by Ryue Nishizawa

2006: Madrid-Barajas airport by RSHP and Estudio Lamela

2007: Oslo Opera House by Snøhetta

2008: Museum of Islamic Art by I M Pei

2009: Murray Grove by Waugh Thistleton Architects

2010: Burj Khalifa by SOM

2011: National September 11 Memorial by Handel Architects

2012: CCTV Headquarters by OMA

2013: Cardboard Cathedral by Shigeru Ban

This list will be updated as the series progresses.